The Ingredients of Effective Practice

You can spend thousands of hours at the pool table and still stay stuck. Why? Because not all practice leads to progress.

(Image from Chat GPT)

What is the difference between playing pool and practicing pool? What does it mean to practice effectively? In this post, we’ll explore the science behind deliberate practice and how it can help players move beyond the intermediate plateau.

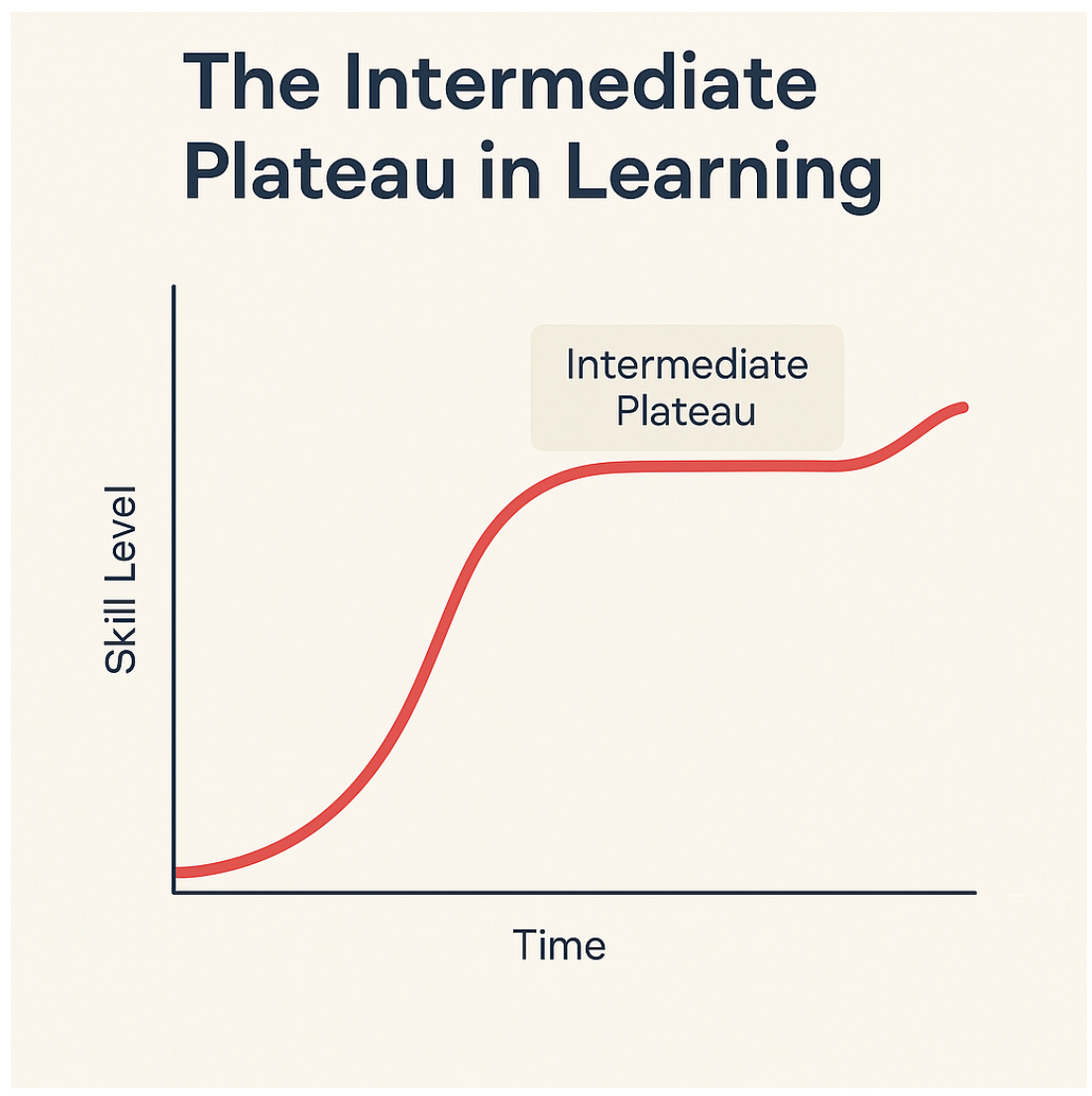

The Intermediate Plateau

Many intermediate players—myself included—can make shots and understand basic position play (i.e., cue ball control). But despite playing regularly for years or even decades, they often remain stuck. Their skills level off, and they don’t reach the advanced level of elite players.

This phenomenon is known in learning theory as the intermediate plateau.

(Image from Chat GPT)

At the beginner stage, players improve rapidly as they struggle to participate in the activity. But once they gain enough competence to play decently, progress slows—or stops. The question becomes: How do you break through?

Beyond the 10,000 Hour Rule

You may have heard the idea that it takes 10,000 hours to master a skill. While it is true that you need lots and lots of practice, not all ‘practice’ is created equally. Back in 2008, famed author Malcolm Gladwell published his book Outliers, and with that popularized the idea of the 10,000 hour rule.

Gladwell explained that if you practiced 4 hours a day for 10 years, you would get to the magical 10,000 hours and, as a result, achieve a level of mastery. Gladwell is a great storyteller and I thoroughly enjoy his books, but he also has a tendency to oversimplify theories for the sake of a good story. His chapter on the 10,000 hour rule was based on the work of Professor Anders Ericsson, who dedicated his life to the study of how people achieve mastery.

In Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise (2016), Ericsson clarifies that deliberate practice—not just any practice—is the true key to mastery.

What Is Deliberate Practice?

In his book, Anderson explores many paths to mastery - the violin, chess, music…The following chart summarizes the key ingredients of deliberate practice.

(Image created by Chat GPT)

Anderson argues that despite the best of intentions, most people do not actually engage in deliberate practice.

How Most Players ‘Practice’

Many players will simply throw some balls out and simply hit them in. Or, they will play a game against themselves just taking turns when they miss. They usually play fast and try to get that wonderful feeling of being ‘in stroke’ - making all their shots.

In these situations, players will typically hit the easy balls in and get that little burst of dopamine (= a reward chemical the brain produces) as the ball goes into the pocket. When they miss, they will grumble and just go onto the next easy shot. So let’s analyze this in terms of the above criteria of deliberate practice:

Ineffective Practice (and Why It Fails):

Taking and making easy shots = not creating a challenging task by practicing more difficult shots or positions that they often miss in games.

Little dopamine bursts = it is enjoyable but doesn’t involve high mental effort or focus

Clearing the table = lots of random different shots without repetition and refinement of specific shots. They are not breaking the game down into ‘subtasks.’ In pool, this would involve isolating specific shots or situations that are challenging for that player.

Missing a shot and continuing = some feedback is present but the player is not thinking about how/why the mistake happened in order to make adjustments - they just keep hitting balls.

Lack of reflection →not reflecting on how the balls are moving or how the stroke/spin happen means that players are not developing new mental representations, which involve being able to see/feel different shots/scenarios in your mind’s eye. This is very similar to the more general concept of Awareness which I discussed in a previous post).

These activities often lack challenge, reflection, and structure—the core ingredients of deliberate practice.

A Better Example: ‘The Mighty X’ Drill

YouTuber Ron ‘The Pool Student’ tackles the intermediate plateau head-on. In his video “How to Improve at Pool / Why Many Players Plateau,” he demonstrates a focused practice exercise called The Mighty X.

(Image from Ron ‘The Pool Student’ video)

What It Involves:

Set up a straight-in stop shot.

Strike the cue ball low to stop it after hitting the object ball.

Use paper reinforcement stickers to repeat the exact same setup.

Why It Works:

Doing a straight stop shot = This is a challenging shot for lower level players. Straight shots like this come up all the time in games and working on this subtask helps players develop their ability to aim and have a smooth straight stroke. It also requires mental effort and focus.

Doing the shot over and over = This involves repetition and the use of immediate feedback to make minor adjustments.

If the ball is not hit perfectly straight it will drift off to the left or right. If he hits too low on the cue ball it will spin backward after impact – too high on the cue ball and it will go forward.

By reflecting and replaying the shot in his head Ron is creating mental representations of the way that type of shot should look and feel like. (note how

Ron uses paper reinforcement stickers to make sure he repeats the same shot each time)

Seeing how many he can get in a row = This type of goal-oriented practice exercise can provide a sense of achievement and satisfaction.

However, it is often hard work and not always enjoyable.

I would also add that this is a way of measuring improvement which can increase self-efficacy - one’s belief in their ability to do a task (see my previous post on ‘Attitude’ for a full discussion of Albert Bandura’s ideas about self-efficacy).

This is deliberate practice in action. Ron has lots of other great videos with practice exercises that I highly recommend!

Practice Smarter, Not Just More

To break the intermediate plateau:

🧱 Return to fundamentals — Are your mechanics solid? Are you missing key details?

🧩 Break skills into subtasks — Work on individual elements (e.g., draw shot, bridge hand stability).

🎯 Target weaknesses — Don’t avoid hard shots—practice the ones you miss.

🛠️ Design intentional drills — Structure practice around your weak areas, not random shooting.

📈 Set goals and track progress — Can you repeat the shot 3 times? 5? 10?

🧑🏫 Get coaching and feedback — A good coach can diagnose issues, provide guidance, and sequence effective practice exercises. (This is what makes practice deliberate versus purposeful, according to Ericsson.)

Summing It Up

There’s a huge difference between playing and practicing. Time on the table is essential—but effective practice needs to be structured, reflective, and targeted.

Deliberate practice is the engine that can drive you beyond the intermediate plateau, helping you build skills, deepen awareness, and develop mental representations of the game.

How about you?

What struck you most in this post about deliberate practice? Are there other points you’d add?

Have you ever experienced the intermediate plateau?

Do you use deliberate practice in your own pool regimen—or in other skills?

I’d love to hear your thoughts. And if you enjoyed this post, a like or a comment is always appreciated!

In upcoming posts, we’ll be looking at different types of practice exercises and what research says about how to create an effective practice routine. Stay tuned!

References

Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The Story of Success. Little, Brown and Company.

Ericsson, A., & Pool, R. (2016). Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.